Net-a-Porter’s Strategy – Why its Struggling Against Rivals

Last year marked the 20-year anniversary of Net-a-Porter. For a long time when one thought about luxury goods shopping online the first name that came to mind was Net-a-Porter. But over time Net-a-Porter’s hold on online luxury shopping has diminished. As Net-a-Porter grew in popularity so did the number of companies trying to emulate its success. From Farfetch, to Mytheresa, to The RealReal, to the brands themselves there is no shortage of places to buy luxury goods online now.

If you are curious about how the online industry for luxury goods is changing and how it’s impacting Net-a-Porter then consider these five factors.

1. Increasing brand power. In a sign of how more power is shifting to brands, Prada recently signed a drop shipping deal with Net-a-Porter. Net-a-Porter which has traditionally had a wholesale model will no longer own the Prada merchandise it sells. Instead, Prada will pay Net-a-Porter a commission on sales. “This is one of the most seismic changes in the retail industry that we’ve seen in decades. There was already a desire from brands to take more control as concession environments have built up more steam over the years. But the pandemic has given brands a chance to re-evaluate their dependency on multi-brand retailers,” says luxury industry advisor Robert Burke.

In the past Net-a-Porter would have purchased Prada goods wholesale and marked them up by a factor of 2.2 or 2.5 in order to make a profit. Commissions in this type of arrangement can range between 20% to 30% but the more power the brand holds the lower the commission it pays. This agreement allows Net-a-Porter to avoid inventory risk including any markdowns it might have to take to move inventory. Since the margins on every sale are lower than in a wholesale model higher transaction volumes are needed to make it work.

In addition to drop shipping becoming a more popular model concessions are also growing in popularity. Farfetch has had an e-concession model from the start. Under this model brands have more control over merchandising, pricing and the customer experience. With more pricing control brands can offer more merchandise at full price, avoiding markdowns which are thought to negatively impact a luxury brand’s image. Brands pay a commission on sales in this model. But ultimately many brands would like to sell through their own channels so they can avoid paying the commission altogether.

2. The growth of luxury marketplaces. Although brands are moving more sales to their own channels, marketplaces are here to stay because consumers like shopping on them. By 2023 it is estimated that marketplaces will have a 14% share of luxury sales up from 6% in 2019. During that timeframe sales coming from brand owned channels will rise to 11% by 2023 up from 5% in 2019.

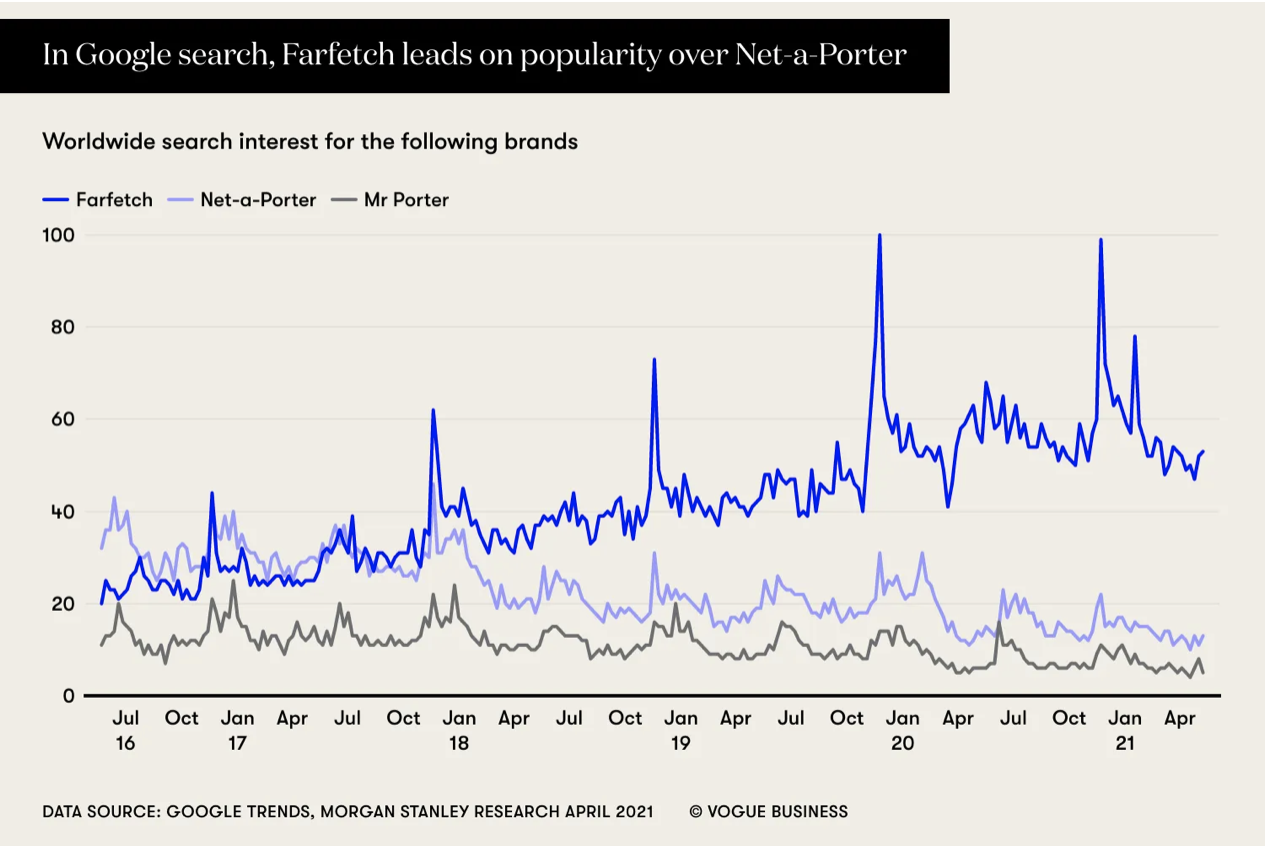

3. More brands are selling direct to consumer. At one time Net-a-Porter, which launched in 2000, was the only game in town. But over time the market for luxury shopping has become more crowded with the entry of online luxury shopping sites like Mytheresa which launched in 2006 and Farfetch which launched in 2007. Then luxury brands decided they wanted to be more reliant on their own channels. For example, Gucci and Prada now generate 85% and 90% respectively of sales from their own channels. All of these channels have chipped away at Net-a-Porter’s dominance over time. Richemont’s eCommerce business which includes Yoox and Net-a-Porter operates at a loss while Farfetch swung to profitability in the first quarter of 2021.

Do you like this content? If you do subscribe to our retail trends newsletter to get the latest retail insights & trends delivered to your inbox

4. Rivals have more power. Seeing the writing on the wall, Richemont, is officially cozying up to its arch rival Farfetch. Last November Richemont along with Alibaba invested $1.1 billion in Farfetch.

“YNAP’s [Yoox Net-a-Porter] revenue growth has been lacklustre compared to peers, particularly marketplace models offering a better consumer proposition in terms of choice of brands, depth of assortment and price,” says Citi managing director Thomas Chauvet. “Add to that over €200m of operating losses annually since the buyout of the YNAP minorities in 2018, it is no surprise to see Richemont management trying to trigger more changes to the business,” said Citi managing director Thomas Chauvet.

“Over the next year we expect YNAP to evolve halfway between the multi-brand/inventory ownership model and the marketplace model, with Farfetch bringing its technology expertise to the table.” This will help YNAP “recruit, regain and retain more customers to the platform, while reducing inventory ownership, which has put significant pressure on YNAP gross margin” Chauvet said.

5. More brands are moving eCommerce in-house. For many years Net-a-Porter has run the eCommerce operations for several luxury brands. But times are changing as brands realize how important it is to manage this strategic asset themselves. Case in point, last year luxury retailer Moncler ended a relationship where Net-a-Porter was running its eCommerce operations and decided to move it in house. “During this time, when attitudes to shopping may be changing and habits may become even more online, I felt we needed not only an evolution, but a revolution in our digital culture,” said Remo Ruffini Moncler’s CEO. Moncler is attempting to increase its eCommerce business to 20% of sales by 2023 from approximately 10% in 2020.

Back in 2018 another one of these strategic relationships came to an end when Kering announced it would be ending an agreement that allowed Net-a-Porter to manage the eCommerce operations of seven Kering brands including: Alexander McQueen and Bottega Veneta. “They don’t want to give all their data to a rival,” said Richie Siegel, the founder of consumer advisory firm Loose Threads. “They need to build out their own expertise; it’s a necessary investment for the future.”